It’s interesting to me that so many ancient cultures named birds by their sound, and I think it’s related to why birds are so relatively easy to sample today: they make noise, and somewhat predictably! When we do point counts, most species are detected aurally. So, in the soundscape, it would have made sense for ancient people to try to mimic the sound when describing what’s around them to others, or discuss the source of their curiosity.

Recognition of birds by sound is immediate in everyday situations, spontaneously available, and, most importantly, a significant feature of the conversations Kaluli have among themselves. Evidence for dominance of the routinely shared character of sound over image categories is manifest in a number of different ways. When presented with pictures or specimens out of context, Kaluli tend first to think of and imitate the sound, then to say the name of the bird. (Feld, 1991, p. 71-72)

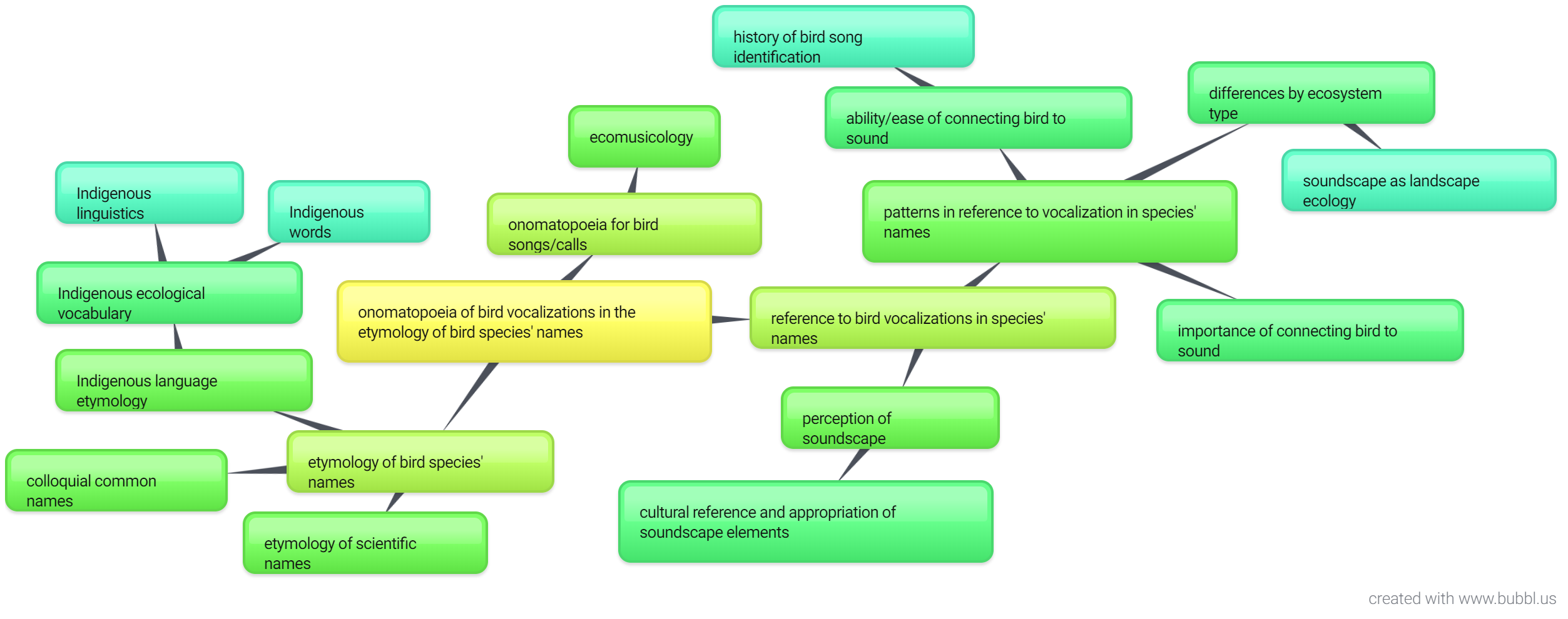

After all, in many cases you may not see the bird, but more likely you’d hear it. An onomatopoeic name for a bird was probably in many cases a more reliable handle to stoke recognition than a visual description, because probably more people heard the bird regularly than necessarily saw it. Add on to that the lack of optics to zoom in on a bird that might be hiding high up! More interestingly to me, there’s evidence in at least some cultures that extended to folk taxonomy, in that birds were grouped in relatedness by sound. Feld noted, “What emerged was a sense of how bird taxonomy intersects with more fundamental daily realities, and most significantly, with sound as a symbolic system.” (1991)

What struck me, though, was how many ancient roots of names reference birds we can see well with the naked eye (e.g. heron), and thus is somewhat the impetus for this blog post. Certainly plenty of names reference physical characteristics, but the contrast interested me between how I perceive and recognize a bird like an egret. I’ve known what that was since I was a child, recognize it visually, and never knew what it sounded like until I took ornithology lab and listened to a recording CD. Yet, its name derives from a sound. To be fair, and non-trivially to this post, I also had the aid of visuals (i.e. a bird guide) before I saw one and recognized it, matching it to a picture and thus a name. How would I have perceived it differently encountering it in the wild sans binoculars, with an interest in describing it to people who may or may not have seen it? Also, that type of observation would have likely been longer, maybe allowing more time for it to vocalize, and thus have the vocalization be a part of my observational experience. For what it’s worth, a bird like a great blue heron has a memorable and surprising call, if you’ve never heard it. I may have been surprised by the quality of the sound, and thus want to imitate it.

On that note, perhaps also the root is less direct or utilitarian. Back in 2010, I remember a conversation with my field tech spurred by our bored mimicry of bird sounds around us. We knew the calls and the species attached, but that didn’t stop of us from enjoying trying to make the sounds ourselves. He commented that it’s “human nature” to try to mimic environmental sounds, and I thought that was interesting. Maybe ancient onomatopoeic names sprung from a mix of entertainment, curiosity and the need for mnemonic regarding the surrounding environment.

Birds meant a lot of things to ancient cultures, just as they do to us today: food, adornment, phenology, religious symbology, mythology/lore, art, aesthetic, etc. So, the soundscape could indicate a variety of things, from basic needs met to the presence of e.g. a spirit. In that sense, I think it would do us (meaning birders) well to sort of deconstruct our typical understanding of the avian soundscape: we listen for birds to identify them. While many ancient cultures indeed mapped vocalizations to species (at least eventually), I wonder how important it was that a sound indicated the presence of a certain species (i.e. not a sought-after game species), as opposed to a changing of the seasons.

To understand how Kaluli hear this world you have to get a handle on what they call dulugu ganalan, or ‘lift-up-over sounding.’ This refers to the fact that there are no single sounds in the rain forest. Everything is mixed into an interlocking soundscape. The rainforest is like a world of coordinated sound clocks, an intersection of millions of simultaneous cycles all refusing to ever start or stop at the same point. ‘Lift-up-over sounding’ means that the Kaluli hear their rain forest world as overlapping, dense, layered. (Feld, 1990)

Many naturalists are likewise well aware of certain bird songs as phenological indicators, not only meaning the arrival of migrants but perhaps changes in resident behavior. The concept I’m attempting to describe, and thus questions I’m trying to form are whether the presence of a bird vocalization was more important, or noticed a.) than in our modern western cultural repertoire and b.) than the need for visual linkage to the source of the sound. I think there’s a strong case for the former: while e.g. North American people of western culture today often recognize raucous, simple, common or interesting bird vocalizations, there would have been more survival incentive (and more cultural reference) for ancient people to recognize a wider suite of bird vocalizations.

Virtually all Kaluli men can sit down in front of a tape recorder and imitate the sounds of at least one hundred birds, but few can provide visual descriptive information on nearly that many. When one hears a bird, and they are by far more often heard than seen in Bosavi, one makes a statement that recognizes the bird through focusing on the sound, attaching the sound to a taxon (the two are often identical, as many taxa are formed from bird call onomatopoeia), and attaching an appropriate cultural attribution to the sound. (Feld, 1991, p. 72)

I remember thinking in high school “I can’t imagine how hard it would be to learn bird calls/songs.” To be fair, I also never took up musical hobbies, so there was very little I knew about distinguishing and describing sounds that couldn’t be turned into words (besides vocal mimicry, which brings this post full circle). Am I especially ill-adept, or would many of my peers agree before trying to learn bird sounds? I think it’s possible we’ve just become disconnected from natural soundscapes and the need to know about them, through both physical walls and what now commands our attention.

Literature Cited

Feld, S. (1990). [Liner notes]. In Voices of the Rainforest [CD]. Bosavi: 360 Productions.

Feld, Steven. “To you they are birds, to me they are voices in the forest.” Sound and Sentiment: Birds, Weeping, Poetics and Song in Kaluli Expression. 2nd ed., University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991.